|

ANT GUESTS

1.1.

Platyarthrus schoblii

Budde-Lund, 1885

(Isopoda, Oniscidea)

This tiny (2-4

mm), whitish woodlouse, is known from the Azores, the north Mediterranean and

Black Sea coasts. It inhabits the nest of several species of ants in the

genera Formica, Lasius, Linepithema and Messor. It was found outside of that region, in Hungary, within the nests of

Lasius neglectus. For a summary update of its distribution and biology

see Tartally et al. (2004) at

Want to see it

alive? Click here:

(video:16”;

2.3 Mb.

View/download).

1.2. Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii Brandt,

1833 (Isopoda,

Oniscidea)

This woodlouse is widely distributed in Europe. It has been detected in nests of

L. neglectus in Belgium (Dekoninck et al. 2007), showing that this

ant is able to host also local woodlouse species. See the distinct aspect of

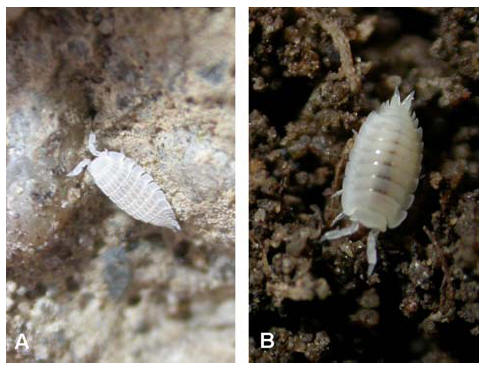

the two Platyarthrus species in the following image.

(Image from Tartally et al. 2004: A: P.

schoblii; B: P. hoffmannsseggii)

2.1. Clytra

laeviuscula Ratzeburg, 1837 (Chrysomelidae)

(Image from

http://culex.biol.uni.wroc.pl/cassidae/European%20Chrysomelidae/clytra%20laeviuscula.htm

)

A few larvae were

found inside the nest of Lasius neglectus at Sant Cugat (Barcelona,

Spain) nesting at the base of a poplar tree (Populus nigra), close to

the railway.

One male eclosed at the

laboratory.

Those larvae are supposed to eat ant eggs and larvae.

2.2. Amphotis

marginata (Fabricius, 1781) (Nitidulidae)

(Image from

www.zin.ru/Animalia/ Coleoptera/rus/ampmarhe.htm )

One beetle was recovered in the nest of Lasius neglectus at

an outpost of the extensive Seva (Barcelona, Spain) supercolony. It feeds by

forcing regurgitation in returning laden workers. If attacked, the beetle

crouches down and is protected by its peculiar cuticular flanges.

3.1. Myrmecophilus

(Myrmecophilus) acervorum Panzer, 1799 (Gryllidae)

Myrmecophilus

crickets are to be found within the nests of many ant species. Female (inset:

ovipositor).

The small, blind

crickets, were found in the nest of L. neglectus from five

populations in Barcelona province: Bellaterra (one female, 2.iv.2003; one

male, 16.vi.2004), Seva (one male, one female, 30.iv.2003), Begues (one

juvenile, 20.x.2005), Badalona (27.ix.2005) and Matadepera (1

male, 3 females, 3 nymphs,

22.x.2009, ) (Espadaler

& Olmo, 2011). Another possible name to apply is M.

myrmecophilus but its status as a good species is still unsettled. Have

a look at those nervous, interesting crickets!

(video:

20”; 2.8 Mb.

View/download).

4.1.

Cyphoderus albinus Nicolet, 1842 (Cyphoderidae)

This springtail has been recently found

in nests of L. neglectus in Belgium (Dekoninck et al. 2007). The

species is a common occurrence within nests of European ants.

(Image

from

http://www.geocities.com/~fransjanssens/taxa/collembo.htm)

|